Inhabiting the architectural envelope

23. February, 2021

Imagine sitting in a deep window with a cup of coffee, watching the life of a city and the passersby;¬ or maybe you are gazing into the forest, to the trees and animals… Either way, you are connected to the outside and the inside at the same time in an inhabitable pocket – you feel you’re somehow part of it.

By Ane Liavaag Ellefsen

Sareh Saeidi is an architect, researcher and teacher, graduated from the Royal Institute of Technology (KTH) in Stockholm and had worked in Iran as an architect for several years. She has taught at Aarhus School of Architecture and is currently Assistant Professor at The Oslo School of Architecture and Design. Last summer she received her doctorate at AHO for the PhD thesis "Inhabiting the architectural envelope. A Design-based Research on Redefining the Climatic and Atmospheric Performances of Architectural Envelop"

When Sareh is asked what her thesis is about, she says that it is more or less about rethinking the position of in-between spaces in architecture through building envelopes. She is invigorating their lost values, questioning why we have lost them when they were in fact very functional. She used to live in an apartment from the sixties in Stockholm that had a cupboard in the kitchen with two fans to the outside making it cold enough to function as her second fridge. “We have lost these very simple solutions, that also contributed to reduce energy consumption”, she says.

Sareh Sahedi received her doctorate from AHO in June 2020. Here with the institute leader of architecture Espen Surnevik and adjudication committee member Halvor Ellefsen.

Architecture working with the climate

Her interest in the field comes from where she grew up, in Iran. A country with architectural traditions in tune with the climate. “Everyone thinks Iran is like a desert, and some people even ask me if we still ride camels. When I was a kid, on road trips, if I were lucky enough, I would see a camel passing by in the desert. I haven’t seen one ever since, which is a pity, and very sad, since it indicates the environmental changes Iran is facing like other places on our blue planet.”Iran has five climatic regions, each with very different conditions in terms of climate and landscape, and therefore different architectural styles. The central part of Iran is warm and dry, and this is mainly where the desserts are. The west is mountainous, with cold winters and lots of snow. The east is a plateau, the north mild and humid with forests, and the south is warm and terribly humid.

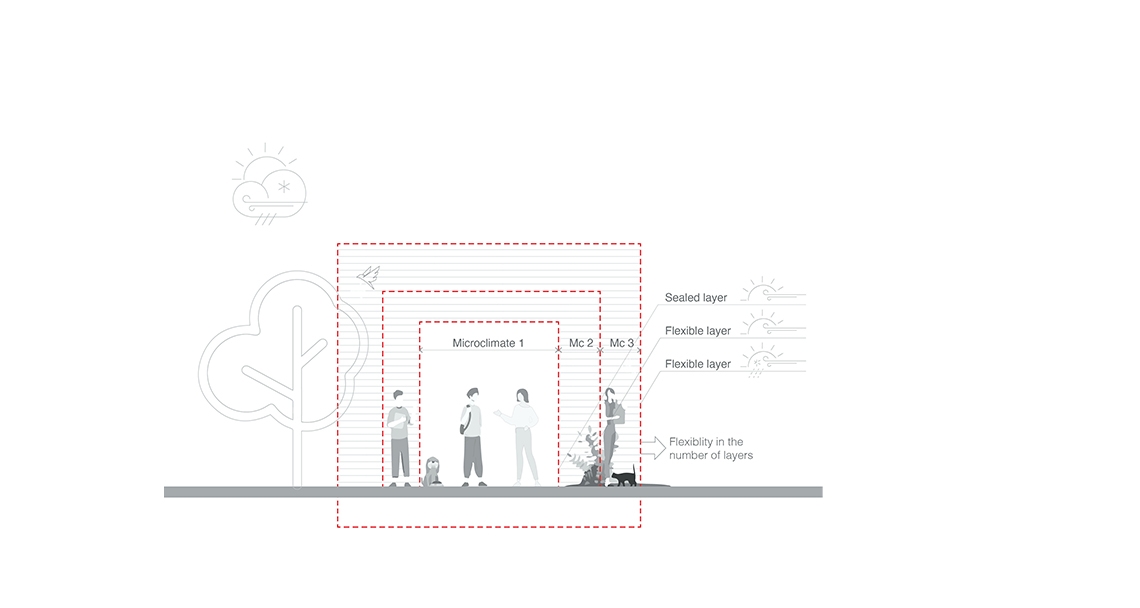

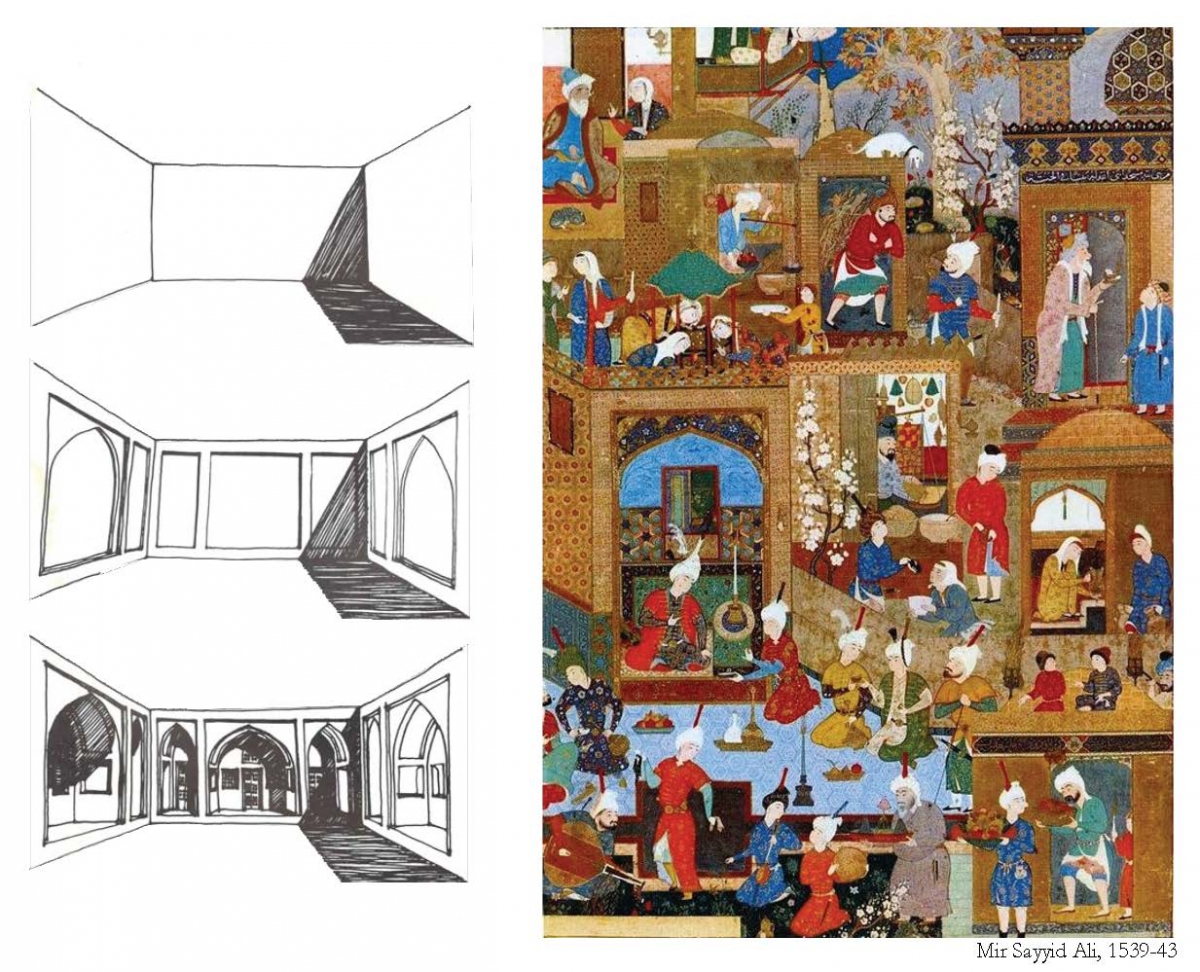

Traditionally, especially in housing architecture, Iranians have met climate with specific design strategies. In the south they have large windows to allow for cross ventilation; in the central regions of Iran, they have courtyards to close off the sandy desert winds, with small gardens inside and fountains to cool the air; this built microclimate is the key to provide comfortable living conditions for the dwellers. They even had natural air condition systems, where the prevailing wind was caught by wind catchers, channelled down, passed by the water fountain, cooled down and then channelled into the rooms. “I love the traditional architecture in Iran. It is very rich and atmospheric to me. And quite the opposite of what is mainly being built there today.”

In-between conditions

The threshold between outside and inside used to provide in-between conditions and an opportunity for the space to be used differently. For example, old houses in Norway had an entrance that was not insulated but sheltered, where you could take off your shoes, store your skies, and then, enter the house. Buffer zones of this kind are not so often in today’s building design anymore. To Sareh, the façade isn’t merely a wall, neither is two dimensional, “it’s a threshold where passing it through is both essential and complementary to the experience of inside and outside”.Throughout history people have constructed and learnt by experience: the vernacular. Instead of fighting for square meters and efficiency, they created comfortable living spaces that also accommodated a degree of flexibility; again, like the semi-insulated thresholds in old Norwegian houses that could be used in different ways throughout the year. “For example, if you have a terrace that is designed to somehow be closed off or opened up, you can use it differently throughout the year. In the winter you can close it off and use it as an extended storage space; and in the summer, you can open it up to enjoy the air and the sun. This might sound too simplistic and functional example, but what I’m trying to highlight here is to advocate for this way of thinking; then, I leave its manifestation to you. What we need more than ever now are ways by which architecture can help us re-connect to the natural cycles and rhythm of climate and to the vegetal and animal worlds. I do believe that this can help to build a collective care for the natural world which is a pressing need in today’s global climate and ecological crisis. It will be a slow change, but a possible one.”, says Sareh. “We have to leave a little bit of space to allow various modes of living in a space, we have to provide enough flexibility in the space so it can adapt to its inhabitants’ needs over time. ”

Not a functionalist

Sareh says that some aspect of her research might imply an attitude that “this is the way, and the only way, to do architecture”, like in functionalistic architecture, where you have a main goal that overpowers everything else – form follows function. She admits that some parts of her thesis could imply that, but she would not call herself a functionalist at all. “Functionalistic architecture is reduced to pure function. My personal interest very much lies in the atmospheres and poetics of architecture, and that is for me outside of, or ideally complementary to, the building’s function.”

Designing conditions for atmospheres

Architects can create conditions for a certain atmosphere to appear. But how the atmosphere happens later in that space is somewhat out of the hands of the architect. You can have a fantastic room with a delightful, beautifully filtered, morning light accommodated by an opening in the wall – the envelope. This is something architects can do, but the atmosphere depends on many other things as well. Firstly, light is different in different seasons, from day to day, and throughout the day, and therefore you will never have a constant atmosphere. Secondly, atmospheres depend on how people use the space – if there are two people arguing in the most beautiful and poetic space, it might not feel like a nice and pleasant space to stay in at all, as opposed to if early in the morning in the same room, a person is sitting alone, listening to the birds or music with a cup of coffee, and perhaps reading a book. Architects can only create conditions, that hopefully will make the space more atmospheric to start with, but what happens after, is yet to come. Atmospheres are a difficult topic, because of its roots in subjectivity and phenomenology, which I believe is academically understudied in the field of architecture.

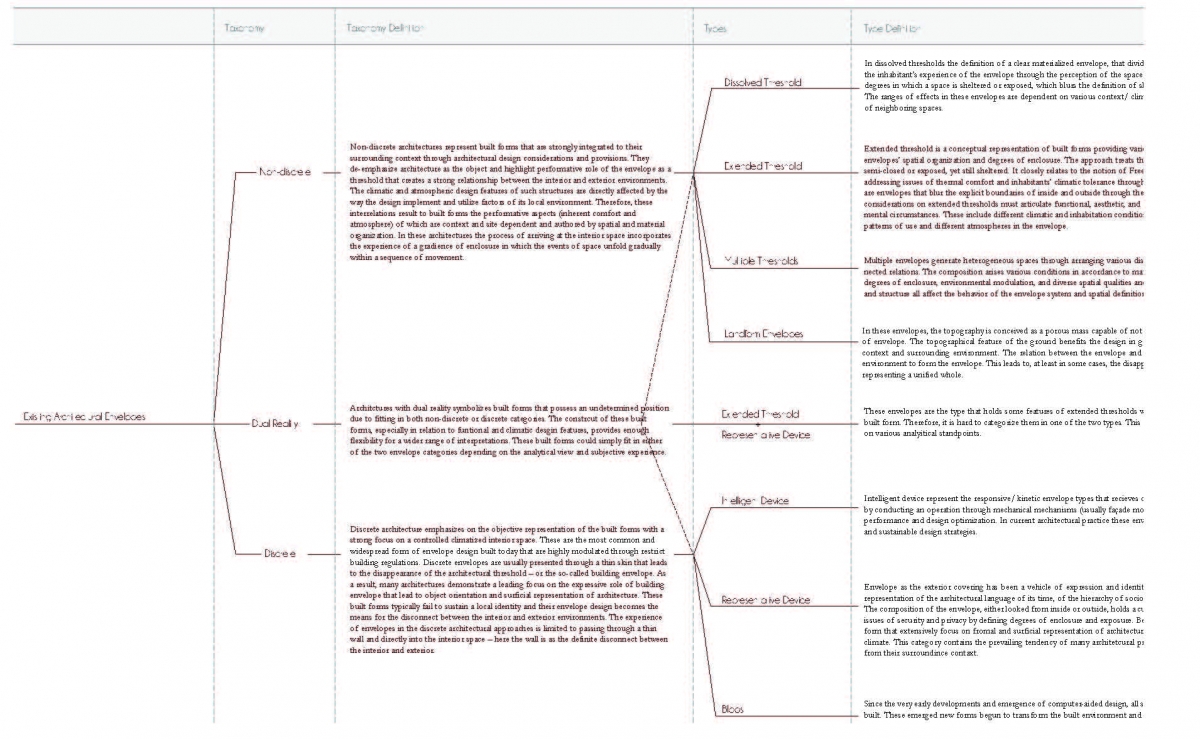

Saeidi, S. (2020). Taxonomy of architectural Envelope. In Inhabiting the architectural envelope: A design-based research on redefining the climatic and atmospheric performances of architectural envelope. The Oslo School of Architecture and Design.

Taxonomy of envelopes

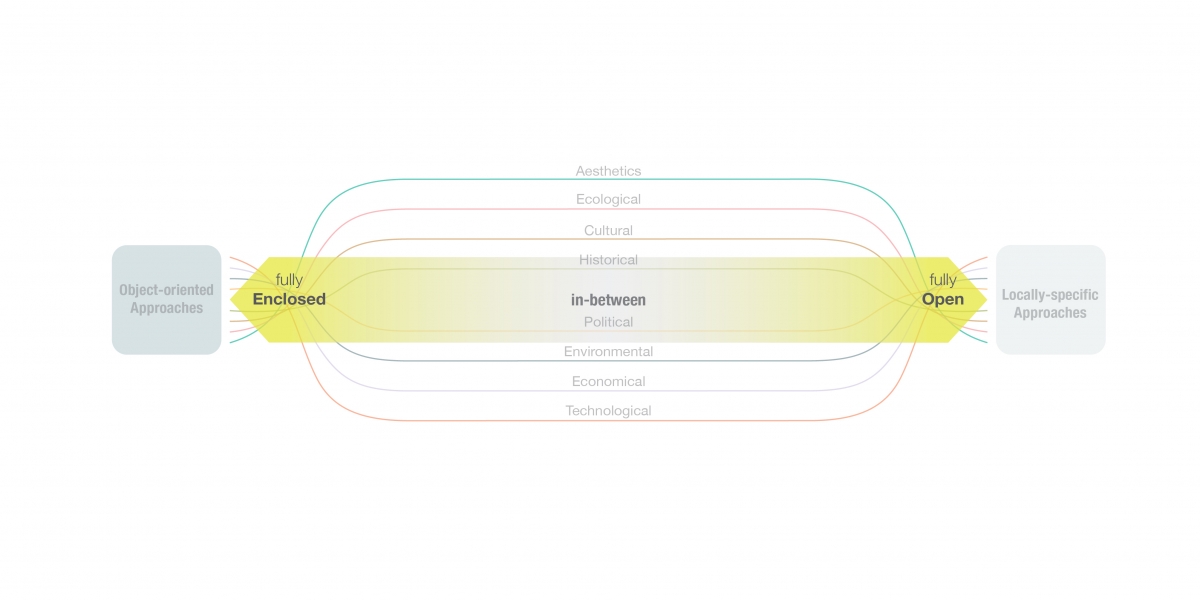

In her thesis, Sareh distinguishes different types of building façades, or envelopes, through an envelope taxonomy based on historical and contemporary built case examples.“I categorized the existing approaches to designing building envelopes into three. Two of these approaches are at opposite ends, and the third is placed somewhere between these two ends – perhaps you could say in the middle of the two”. Now, however, she sees it differently. Throughout the study of taxonomy, she learnt that analyzing a building as completely closed nor completely open is rather difficult - because various in-between conditions of the designs could actually be interpreted differently. “I no longer see the two ends as concrete ends; they have built a gradience to me now. The two approaches represent, as presented in my thesis, on the one hand, building façades that are the most enclosed – like the designs I was criticizing for shielding off the building from the exterior and then, loading the envelope with mechanical systems to provide interior living comfort. And on the other, building façades that have a porous structure, allowing the exterior environment (for example of the weather or buildings’ immediate exterior) to directly affect the inhabitable space of the envelope. Now it is the in-between range of these two ends that attracts me and is a realm I would like to explore further.”

Sareh hopes her thesis makes students and colleagues start questioning how to look at the design of the building envelope a little differently, and beyond the most common practice of today’s architecture. She also hopes it provokes enough questions for researches to pick up on and develop the topic further.

Saeidi, S. (2020). Approaches to Architectural Envelopes.