Diploma project

Spring 2022

Institute of Urbanism and Landscape

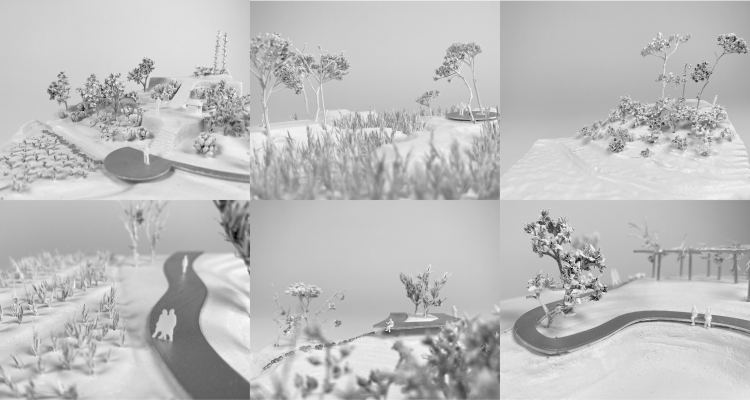

The fluid garden of Kitakami is an experimental project that rethinks adaptive disaster lifestyle in the coastal area of Japan where a Tsunami hit communities in 2011. The approach is to weave several aspects of traditional Japanese culture to design a new resilient landscape that celebrates natural cycles and understands humans as part of them.

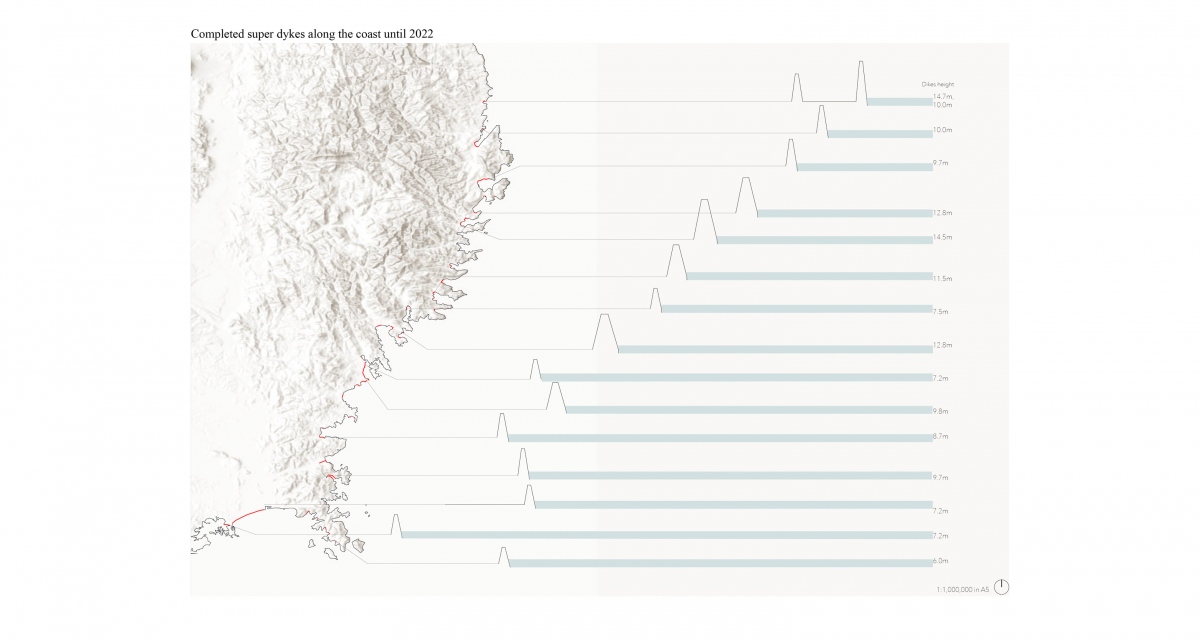

Shortly after the disaster, the reconstruction process was top-down; the government planned the reconstruction budget and quickly implemented the same generic super-dike design for every municipality to trigger fast economic recovery. However, the seawalls do not prevent the Tsunami from hitting the settlements. Instead, it delays the arrival of the giant waves, increasing the time available to evacuate the local populations. On the other hand, the seawalls have not improved the surrounding natural environment in the long term; at the same time, it has puzzled the land use of the locals since the crops, and the soil behind the dikes will still be hit by the saltwater eventually. Moreover, most plans are not well thought through, as all the walls had to be finished before 2020; thus, many of the quickly built constructions are not well fitted to specific site’s needs and realities; their efficacy is also questionable.

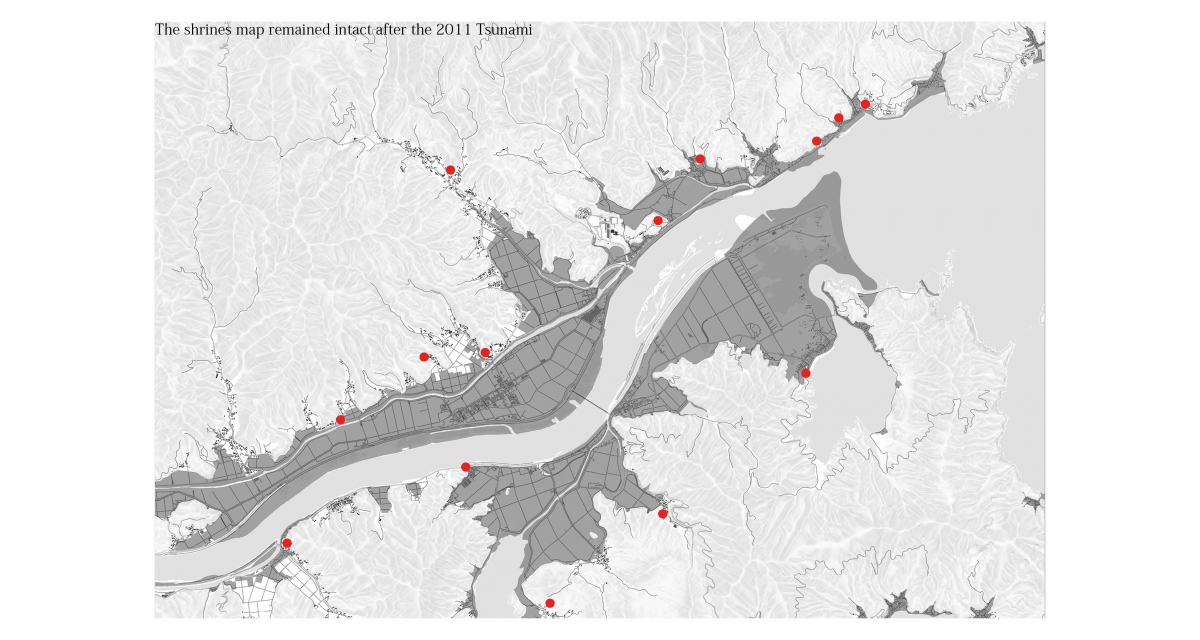

The proposal explores how people could deal with the natural disaster cycles of the Tsunami coast by using traditional knowledge. The seawall solution ignores ancient Japanese cultural practices, as it relies on a rigid tool that aims to fight nature rather than dialogue with it and explore the dynamics of Tsunami landscapes. This dialogue between humans and the natural forces is based on Japanese traditions. In a proverbial way, most of the Shinto shrines in the disaster area remained intact when the Tsunami hit – as it reached the inland area, many of the shrines were standing on the very edge of the waves. Most of these constructions were dedicated to Susanoo or its relative deities, the gods of water, sea, storm, and pestilence.

Ancient knowledge as an emergency route

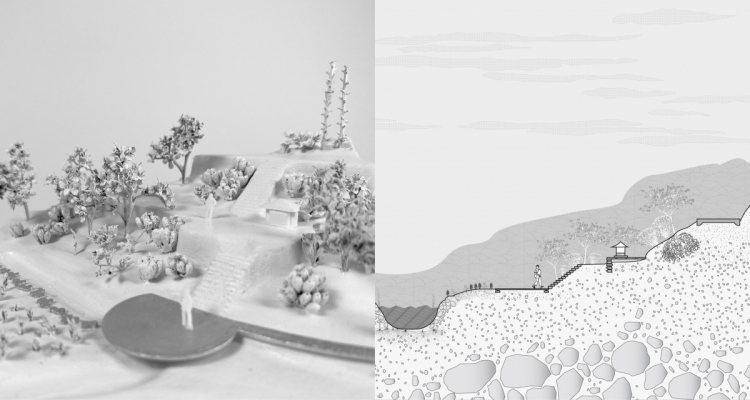

The first strategy is to create an emergency path based on the mapped shrine locations. Today the main road connecting the ria is at the edge of the land with the water, right behind the seawall; in case of a Tsunami, the road would be blocked for several days. Therefore, I place a new emergency path connecting the shrines of the valley along the 8 meters contour, the “ancestral safe zone.” It is a small road, wide enough for emergency vehicles to drive through.

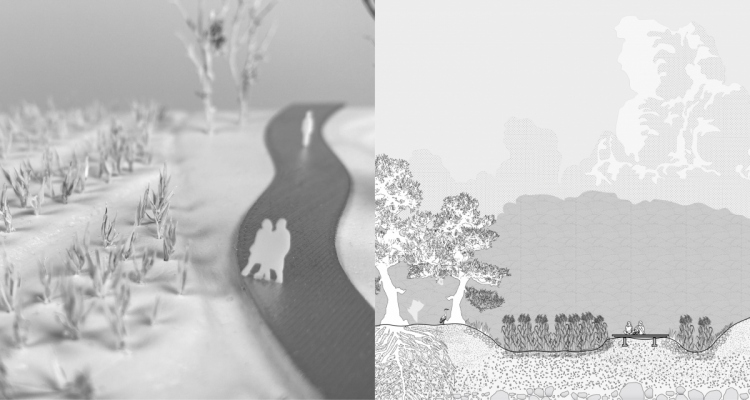

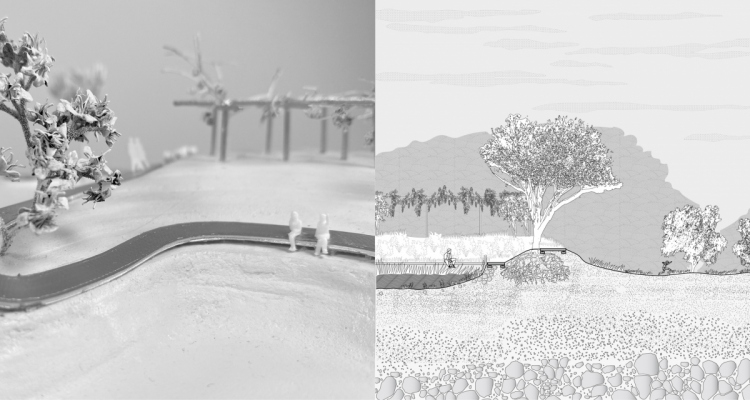

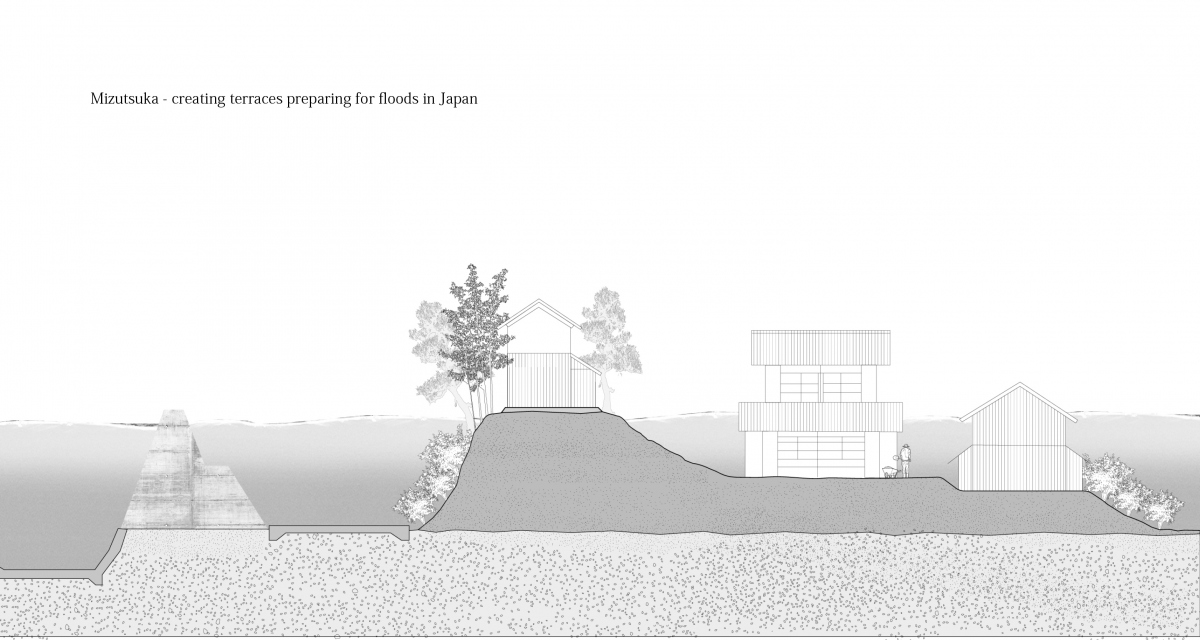

From fighting nature to absorbing and caring

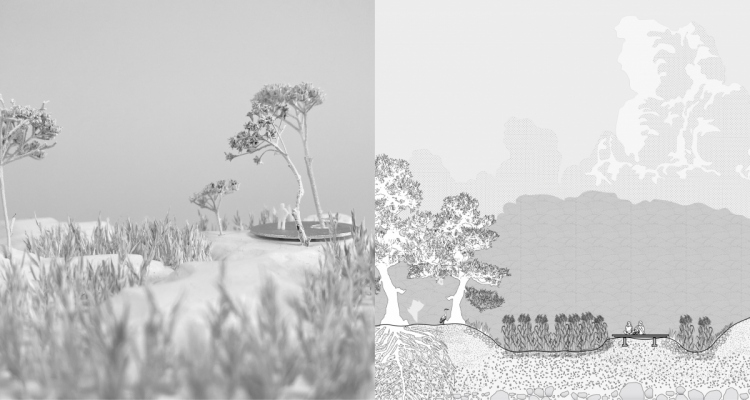

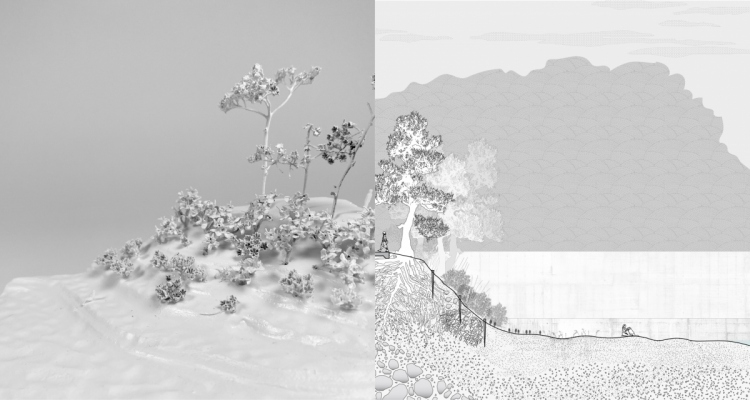

This strategy is inspired by the Japanese traditional technique of Mizutsuka, developed by people in an area that suffers extreme seasonal floods. They terraced the land, creating different flood levels where constructions and plantations were adapted to the natural fluxes. I propose to adopt the topography of Kitakami into different micro-terraces according to their exposure to Tsunami saline waters. The first or lower level would be the brackish-water reed habitat, historically utilized by locals as a roofing material. The second level will be used as a recreational garden to test crops’ resistance to temporary saline flood; the residents will join in creating the garden. The third terrace, above the 8 meters contour, would be the rice field and orchard. Keeping rice production above the safe height allows continuing current food production practices while cultivating other species that can also be used for economic turn-out. Above the fertile plain, a new forest edge is created by planting deciduous trees like Oak and Maple. Clearing up and planting new species is a strategy to renew the monoculture of cedar and cypress, as it has deteriorated the water quality in the area. Although all the species re-introduced have been traditionally used for production, I aim to inspire a possible circular, diversified and resilient economy to counter the current fragile rice-monoculture in the valley.

Animistic celebration of natural cycles.

Japanese animism is all about natural cycles, interacting, and living with them. People worshiped natural elements such as forests, rivers, mountains, rocks, waterfalls, and trees in ancient Japan. The religion called Shinto is practiced in the area and is still today the substrate of mainstream Japanese beliefs. This understanding of the world is embedded in traditional design practices that take inspiration from observations of landscape scenery, such as the traditional dry gardens. As an homage to this creative practice, the new topography of the gardens is carefully shaped through the figure of the Matushima archipelago, a worshiped landscape in the same prefecture as Kitakami. Different water level scenarios are considered, and the garden will change its appearance through water from time to time. Spaces designed for people to meet natural phenomenology are created, such as two spots to observe the solstice sunlight and sunset, the traditional “hour of the gods.” The observation points will disappear when the first levels of flood happen, manifesting the fluid nature of the landscape.

Shizuka Miura / Shizuka6434@gmail.com / Portfolio link