The Impact of Deconstructivist Architecture

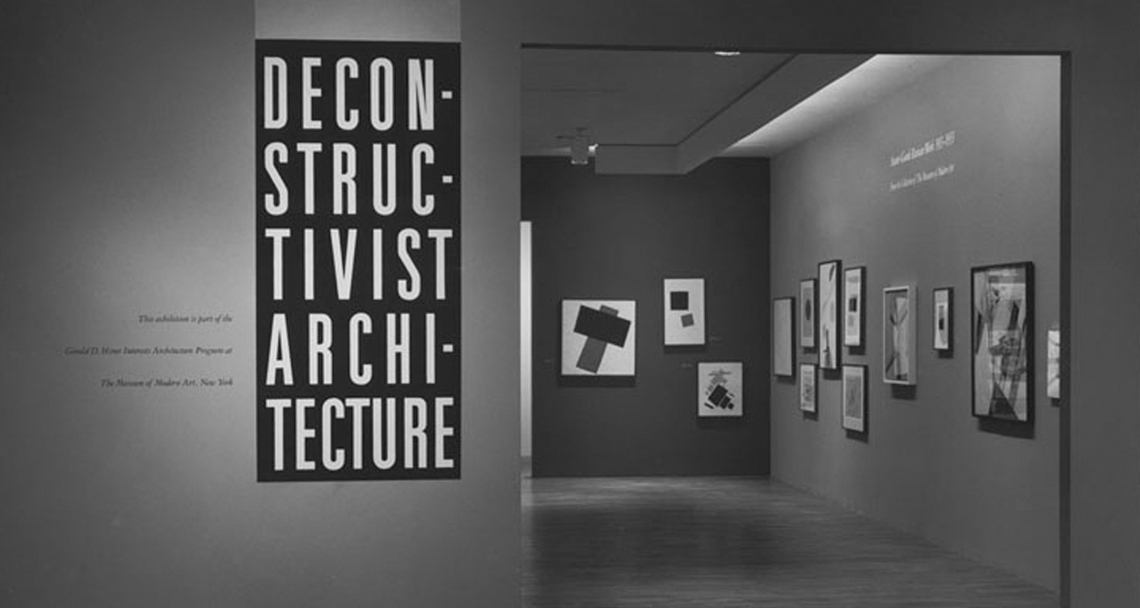

The 1988 Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, curated by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley, was a minor exhibition that forced architecture to change directions.

Charting the ten years leading up to the exhibition and the reception before and after the show, the new AHO PhD thesis by Tina Di Carlo The Construction of an Exhibition within Architecture Culture looks at the apparatus of the exhibition to question what the exhibition constructed and what in turn constructed it.

Charting the ten years leading up to the exhibition and the reception before and after the show, the new AHO PhD thesis by Tina Di Carlo The Construction of an Exhibition within Architecture Culture looks at the apparatus of the exhibition to question what the exhibition constructed and what in turn constructed it.

In conjunction with her doctoral thesis defense, Di Carlo answered some questions regarding the myth and the force behind this soon to be 30-year-old exhibition.

Why did you choose to study this exhibition?

I wanted to choose something that was very topical and current, looking at the very next movement within architecture culture. At first I was going to look across three institutions –The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt– but this proved to be too large a topic, so in the end I chose to focus on just the one exhibition. And, in doing this, I wanted to choose an exhibition around which a certain myth had been created.

Modern Architecture: International Exhibition Philip Johnson’s first exhibition and on that which Terence Riley had written in Exhibition 15: The International Style became a model and choosing Johnson’s last exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture became compelling.

Is exhibiting architecture different to exhibiting other cultural expressions?

Yes, I think so. Architecture is difficult because one is never working in the medium itself, but is also working with other media to represent, for better or worse, their thinking and the development of a project. This is something that is very difficult to convey to a general audience, and the modes of production, I would argue, test the very limits of what it means to display architecture. This has been a subject of great debate over the last fifteen years, and one of the reasons I chose to study at AHO. The grant for Place and Displacement: Exhibiting Architecture allowed one great depth through which to study making exhibitions within architecture culture.

You say the exhibition constructed an apparatus, and was constructed by an apparatus; in what way do these constructing elements interact, what do they generate?

All of the elements of the apparatus – the media, installation, catalogue, symposia, and the stakeholders – must interact and in the case of Deconstructivist Architecture, interacted to canonize this event, despite the fact that the curators denied just such an intent. Foucault mentions that there is no inside nor outside to an apparatus – and so too here, it is a relational structure between these elements that could account for the shift. The curators – Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley, for example, could be considered as two of the primary stakeholders. Their power to choose who would be in and who would be out, played a great part in the making of history and the exhibition and it was a substantial part of the apparatus. Likewise the branding of the event – through both the term deconstructivism itself and the black and red logo – one could argue had a significant role in the repercussions of the exhibition as a particular, pivotal and historical event, as a movement, let’s say. But in general, what all these elements generated was debate and outrage; and these polemics fueled the press, which became not only a crucial element in the apparatus but in constructing a cultural shift.

The proliferation of discourse created by this exhibition, could you say a little more about this. What happened, who took part, what marks did it leave? How does this take a new direction from previous history of exhibitions?

The discourse created by the exhibition started, as Mark Wigley would state as his desire for the symposium, an argument. Part of the point of this, and as again would be stated at the symposium, was to reinvigorate what critics had called the socially bankrupt and moribund discourse of architecture – at the time, this was late postmodernism that had been absorbed into the market. The key players in the polemics were both Johnson and Wigley, but also the critics and scholars in the press became pivotal. Voices such as Michael Sorkin, Catherine Ingraham and Sylvia Lavin all took part, as did many journalists from the more popular press.

Could you say something more about the critical tools and analytical strategies of Deconstructivist Architecture.

The critical tools and analytical strategy of the exhibition functioned and played out in what would be called a very deconstructivist scenario. Things that were denied on the one hand, were reaffirmed on the other and through the very same apparatus that was in play. Thus, and for example, while the curators claimed in the wall text that “[this is not a movement. This is not a single-minded stylistic vision of the future” it was this – through the naming of the exhibition and the homogenizing effects, for example, of the black and white photography that made all the projects look similar – that happened. In fact It could be said that it happened even more strongly because of their very denial – such a denial fueled the polemics and debate within the press.

What is the scene now with architecture shows and exhibitions?

I would say it is much broader. It has once again exploded into the international scene and culture at large. There are myriad institutions that are taking on architecture exhibitions within an art setting – from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Serpentine and Hauser & Wirth in Somerset, England – and I think this is doing a lot to invest in the discourse of architecture and make it more understandable, more approachable to the general public. And there are a host of biennales and triennials now, in Oslo, Lisbon and Chicago, just to name a few.

Why did you choose to study this exhibition?

I wanted to choose something that was very topical and current, looking at the very next movement within architecture culture. At first I was going to look across three institutions –The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt– but this proved to be too large a topic, so in the end I chose to focus on just the one exhibition. And, in doing this, I wanted to choose an exhibition around which a certain myth had been created.

Modern Architecture: International Exhibition Philip Johnson’s first exhibition and on that which Terence Riley had written in Exhibition 15: The International Style became a model and choosing Johnson’s last exhibition Deconstructivist Architecture became compelling.

Is exhibiting architecture different to exhibiting other cultural expressions?

Yes, I think so. Architecture is difficult because one is never working in the medium itself, but is also working with other media to represent, for better or worse, their thinking and the development of a project. This is something that is very difficult to convey to a general audience, and the modes of production, I would argue, test the very limits of what it means to display architecture. This has been a subject of great debate over the last fifteen years, and one of the reasons I chose to study at AHO. The grant for Place and Displacement: Exhibiting Architecture allowed one great depth through which to study making exhibitions within architecture culture.

You say the exhibition constructed an apparatus, and was constructed by an apparatus; in what way do these constructing elements interact, what do they generate?

All of the elements of the apparatus – the media, installation, catalogue, symposia, and the stakeholders – must interact and in the case of Deconstructivist Architecture, interacted to canonize this event, despite the fact that the curators denied just such an intent. Foucault mentions that there is no inside nor outside to an apparatus – and so too here, it is a relational structure between these elements that could account for the shift. The curators – Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley, for example, could be considered as two of the primary stakeholders. Their power to choose who would be in and who would be out, played a great part in the making of history and the exhibition and it was a substantial part of the apparatus. Likewise the branding of the event – through both the term deconstructivism itself and the black and red logo – one could argue had a significant role in the repercussions of the exhibition as a particular, pivotal and historical event, as a movement, let’s say. But in general, what all these elements generated was debate and outrage; and these polemics fueled the press, which became not only a crucial element in the apparatus but in constructing a cultural shift.

The proliferation of discourse created by this exhibition, could you say a little more about this. What happened, who took part, what marks did it leave? How does this take a new direction from previous history of exhibitions?

The discourse created by the exhibition started, as Mark Wigley would state as his desire for the symposium, an argument. Part of the point of this, and as again would be stated at the symposium, was to reinvigorate what critics had called the socially bankrupt and moribund discourse of architecture – at the time, this was late postmodernism that had been absorbed into the market. The key players in the polemics were both Johnson and Wigley, but also the critics and scholars in the press became pivotal. Voices such as Michael Sorkin, Catherine Ingraham and Sylvia Lavin all took part, as did many journalists from the more popular press.

Could you say something more about the critical tools and analytical strategies of Deconstructivist Architecture.

The critical tools and analytical strategy of the exhibition functioned and played out in what would be called a very deconstructivist scenario. Things that were denied on the one hand, were reaffirmed on the other and through the very same apparatus that was in play. Thus, and for example, while the curators claimed in the wall text that “[this is not a movement. This is not a single-minded stylistic vision of the future” it was this – through the naming of the exhibition and the homogenizing effects, for example, of the black and white photography that made all the projects look similar – that happened. In fact It could be said that it happened even more strongly because of their very denial – such a denial fueled the polemics and debate within the press.

What is the scene now with architecture shows and exhibitions?

I would say it is much broader. It has once again exploded into the international scene and culture at large. There are myriad institutions that are taking on architecture exhibitions within an art setting – from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York to the Serpentine and Hauser & Wirth in Somerset, England – and I think this is doing a lot to invest in the discourse of architecture and make it more understandable, more approachable to the general public. And there are a host of biennales and triennials now, in Oslo, Lisbon and Chicago, just to name a few.