Diplomprosjekt

Høst 2024

Institutt for arkitektur

Lindåstunet is an obsolete health institution in Alver Municipality. It was originally designed as a tuberculosis home by the architect Lilla Hansen, known as the first practicing female architect in Norway. Lilla Hansen burnt her own archive before she died, leaving much of her work and legacy fragmented and shrouded in mystery. Lindåstunet remains as a rare example of her work and is possibly emblematic for our understanding of her contribution to the development in health care architecture.

Building on its legacy as a health institution, the project repurposes the building as a municipal care unit, to alleviate pressure on centralized hospitals, to bring healthcare closer to patients’ home districts, and to propose a dissent to the conventional views on the architecture of care.

The abandoned building stands today as a testament to the evolution of healthcare architecture, where modernization, advances in medical technology, and an increasing focus on efficiency have driven changes in hospital design. This shift has culminated in the centralization of healthcare facilities and the abandonment and demolition of historic health institutions. This development poses a threat to patient safety, as corridor patients have become more common, travel distances for treatment have increased, and the pressure for efficiency is leading to rapid patient discharges.

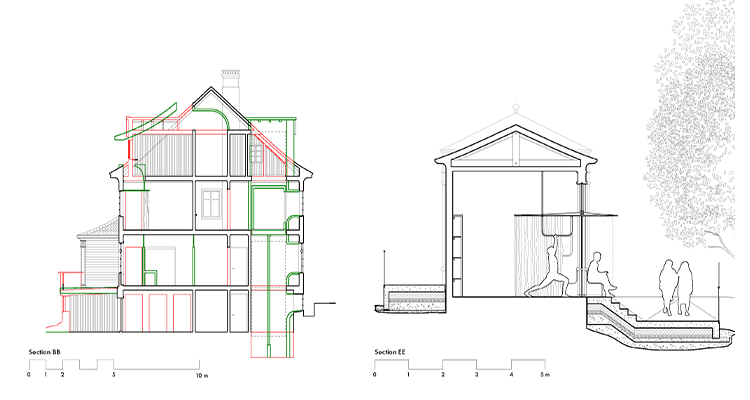

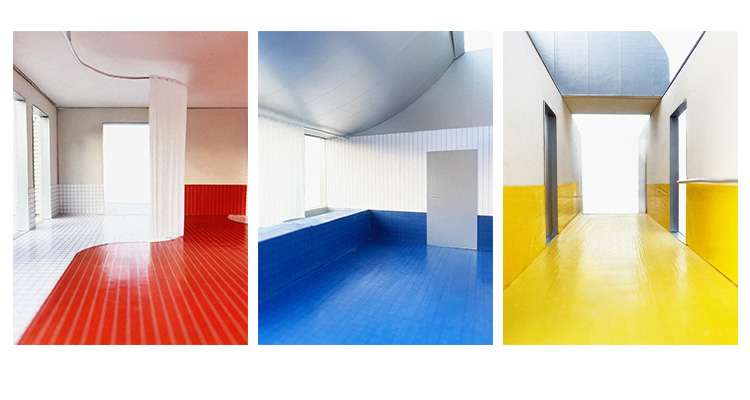

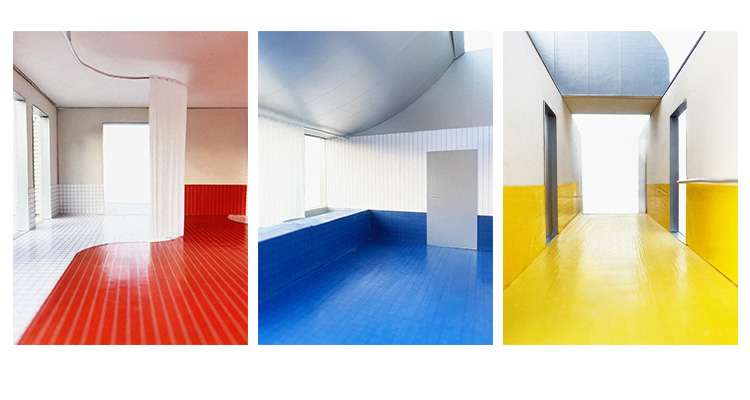

The project explores the potential of adapting the building for a new health program, critically evaluating how its existing architectural features—such as natural light, surrounding environment, interior colors, and spatial organization—can be preserved and enhanced, while addressing deficiencies like restroom facilities, circulation, and access to outdoor spaces. It also considers the needs and comfort of the people who will use the space, taking into regard the need for accessibility, ergonomic layouts, and spaces that foster social interaction, while examining how light, color, and spatial arrangement can cultivate a sense of safety and tranquility. Exploring the topic of the individual and the relation between the private vs the exposed, the project proposes an alternative view on the arrangement of spaces in health care buildings, creating a health facility with spaces for privacy and comfort that does not exclude the need for social encounters.

In 2014, the nursing home was abruptly closed, forcing residents to relocate with less than six weeks’ notice. This hasty eviction resulted in a chaotic scene of personal belongings, furniture, and equipment that are still left behind. The remaining inventory in the building conveys a sense of homeliness, providing a contrast to the institutional atmospheres of modern hospitals. The project seeks to preserve these domestic qualities by examining the use of materials that blend the softness of light and fabric with harder, more hygienic elements. It also examines the use of curtains as a room-dividing element that provides flexibility and self-determination, creating private spaces, filtering light, and emphasizing the thresholds between private and common areas.

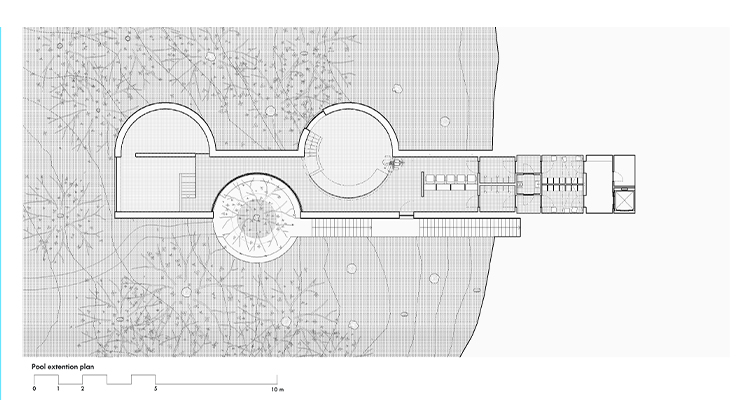

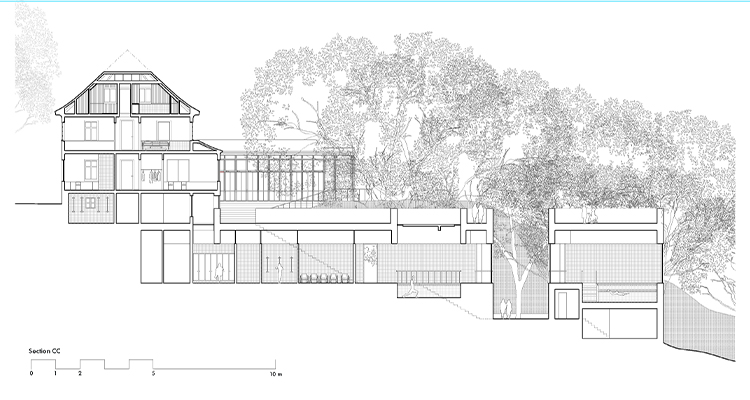

The different buildings on the site is treated as separate units, each serving a specific purpose: the main house as the care unit, the sun terrace extension as a treatment space, and the training pool as an individual elongated extension serving its own specific program - a continuation of the logic and hierarchy of the tuberculosis home’s sun terraces, seen as individual objects in relation to the main building. The training pool extension is placed to emphasize the surrounding landscape’s diverse qualities, making the garden and forest areas accessible to patients, visitors, and residents.

Rakel Emilie Emhjellen Paulsen / rakelep@gmail.com / +47 480 77 258

The abandoned building stands today as a testament to the evolution of healthcare architecture, where modernization, advances in medical technology, and an increasing focus on efficiency have driven changes in hospital design. This shift has culminated in the centralization of healthcare facilities and the abandonment and demolition of historic health institutions. This development poses a threat to patient safety, as corridor patients have become more common, travel distances for treatment have increased, and the pressure for efficiency is leading to rapid patient discharges.

The project explores the potential of adapting the building for a new health program, critically evaluating how its existing architectural features—such as natural light, surrounding environment, interior colors, and spatial organization—can be preserved and enhanced, while addressing deficiencies like restroom facilities, circulation, and access to outdoor spaces. It also considers the needs and comfort of the people who will use the space, taking into regard the need for accessibility, ergonomic layouts, and spaces that foster social interaction, while examining how light, color, and spatial arrangement can cultivate a sense of safety and tranquility. Exploring the topic of the individual and the relation between the private vs the exposed, the project proposes an alternative view on the arrangement of spaces in health care buildings, creating a health facility with spaces for privacy and comfort that does not exclude the need for social encounters.

In 2014, the nursing home was abruptly closed, forcing residents to relocate with less than six weeks’ notice. This hasty eviction resulted in a chaotic scene of personal belongings, furniture, and equipment that are still left behind. The remaining inventory in the building conveys a sense of homeliness, providing a contrast to the institutional atmospheres of modern hospitals. The project seeks to preserve these domestic qualities by examining the use of materials that blend the softness of light and fabric with harder, more hygienic elements. It also examines the use of curtains as a room-dividing element that provides flexibility and self-determination, creating private spaces, filtering light, and emphasizing the thresholds between private and common areas.

The different buildings on the site is treated as separate units, each serving a specific purpose: the main house as the care unit, the sun terrace extension as a treatment space, and the training pool as an individual elongated extension serving its own specific program - a continuation of the logic and hierarchy of the tuberculosis home’s sun terraces, seen as individual objects in relation to the main building. The training pool extension is placed to emphasize the surrounding landscape’s diverse qualities, making the garden and forest areas accessible to patients, visitors, and residents.

Rakel Emilie Emhjellen Paulsen / rakelep@gmail.com / +47 480 77 258