Diplomprosjekt

Høst 2022

Institutt for arkitektur

From Drammensveien 312 to Arnstein Arnebergvei 31

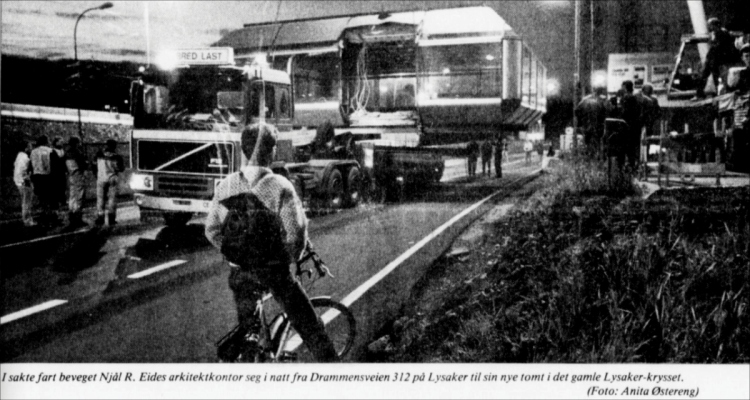

Som en flyvende tallerken i sakte film letter romfartskontoret til Njål R. Eide fra sin plass på Drammensveien 312 på Lysaker sentrum halv ett i natt. Noen timer senere var det på plass på sine søyler på fjellknausen i det gamle fornebu-krysset.

Asker og Bærums Budstikke, 7. July 1990

Around midnight, a Tuesday in July 1990, a 107 square meter silver box of steel, aluminum, and glass, colloquially called the UFO, took off to a new destination, blocking the E18 Highway in the process. A service module was disconnected before the 10-ton building was lifted by a crane and onto a truck, and three hours later, 700 meters down the road, it landed on its new foundation. The spectacular event, which was extensively documented, with journalists referring to it as something out of a science fiction movie, is the starting point for my diploma project.

Because of the development of Lysakerlokket, a large-scale infrastructural project, Njål R. Eide’s eye-catching architectural office was forced to move elsewhere. Eide initiated the pavilion in 1978 as a prototype for large modular buildings for his two primary sectors of operation: cruise ships and oil platforms. An optimistic belief in a future where technology and mass fabrication played an important role was incorporated into the design. The office pavilion rested on four concrete pillars, 60 cm above ground, on leased land. It had a 25-square-meter service module connected to it, containing an entrance area, technical installations, and water. The office pavilion was built to move.

The unusual event on E18 more than 30 years ago is relevant for an architectural project today because the building in question is an unresolved issue – it currently lies vacant and derelict with no future plan. I will reveal through my diploma project that the building reflects a fascinating, multi-layered history. It is an heirloom from the recent past with a direct link to the oil industry and Norwegian cruise-ship design, two problematic fields which have shaped Norwegian society from the 1970s onwards. The pavilion’s history as a preservation object on the move also connects it to heritage management, a field in which preserving by moving has been a recurring method since the ambitious attempts to save national treasures such as stave churches and other vernacular buildings in the 19th century, leading to open-air museums, with Folkemuseet, located in Bygdøy, Oslo, as one internationally prominent example.

Eide’s portable office building is not a national icon but a style representative. If we are to nurture a holistic culture of reuse, more buildings from the recent past must be preserved and repurposed. This diploma asks how to restore, reuse, transform or dismantle this and similar structures. I propose to move the office pavilion once again to explore its potential for survival and repurposing. Reactivating a concept of mobility as a source of architectural design and a preservation strategy, the project links the office pavilion to past ideas that might be as valid today as ever.

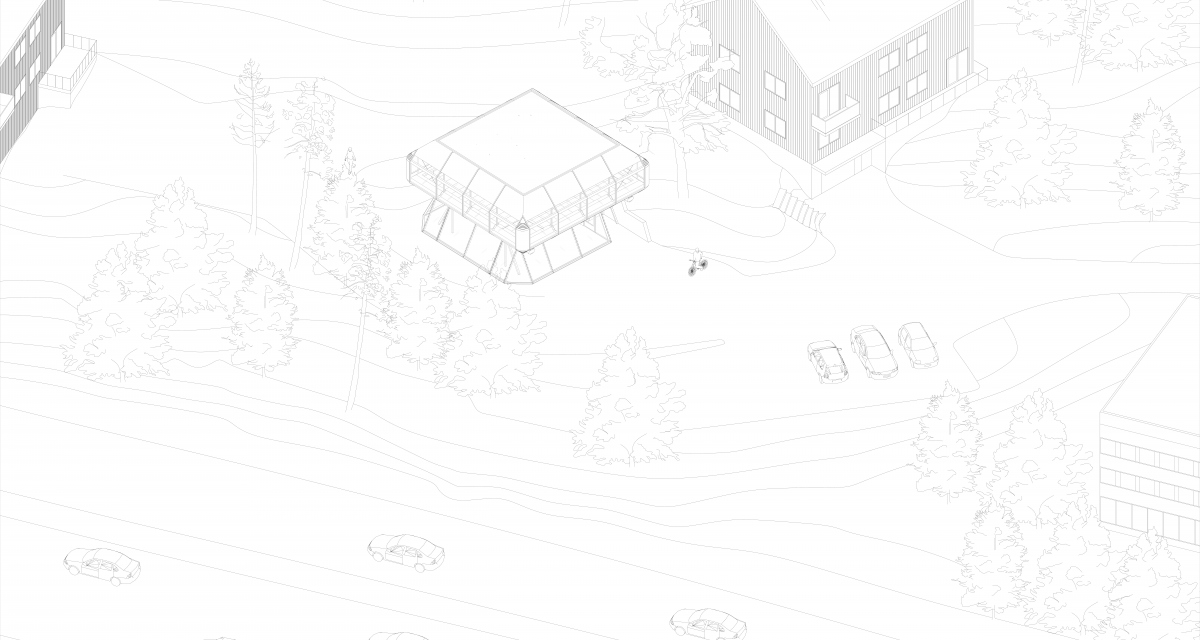

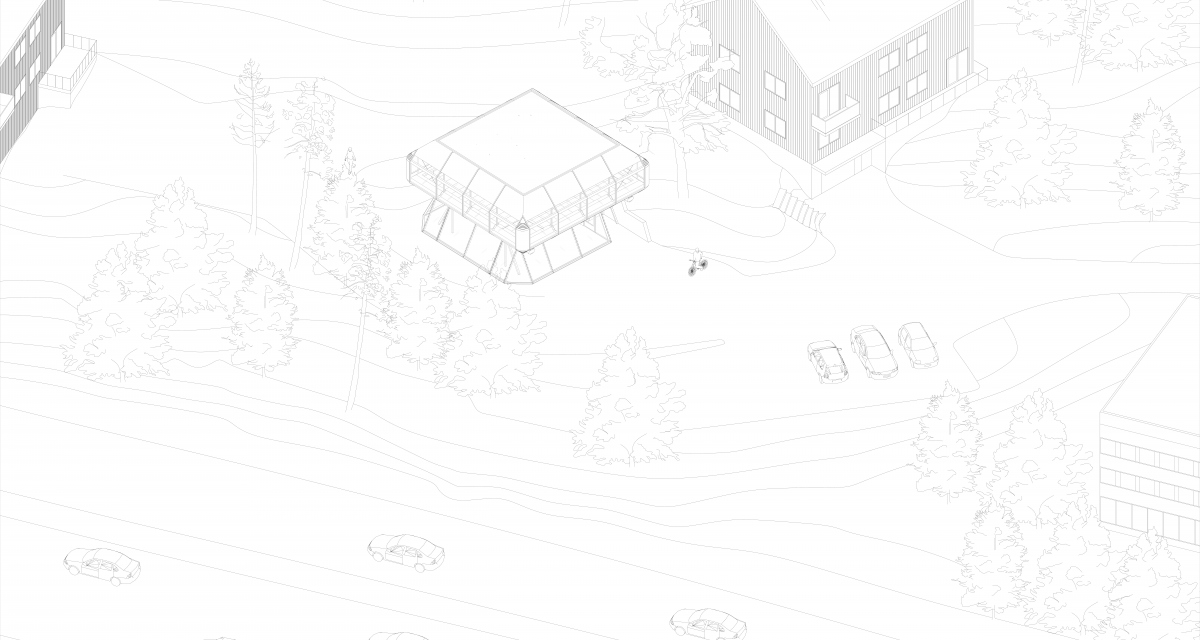

From Arnstein Arnebergvei 31 to Folkemuseet

Today, the building appears as a futuristic ruin - dusty, dilapidated, with punctured windows and full of mold. Forty-four years have passed since its erection, thirty-two years since it was moved, and ten years since it was abandoned. Lysaker is yet again under development, and the building (together with Eide’s archive) and all its surroundings are planned for demolition to make room for new buildings. The easy thing would be to destroy it and forget about it. So why shouldn’t we?

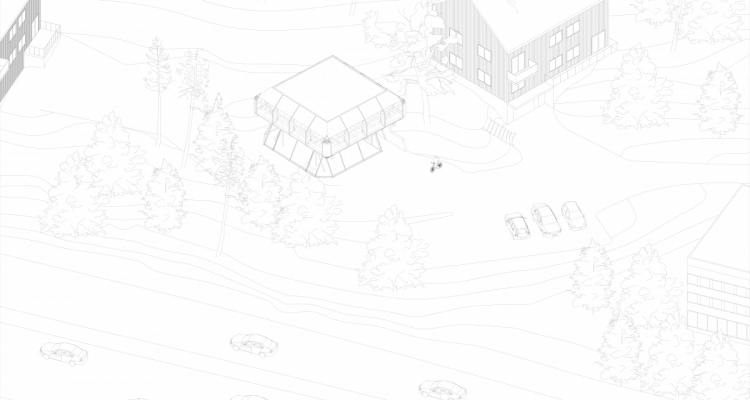

My diploma project proposes moving the building to Folkemuseet as an ex-situ preservation tactic. This will emphasize its importance in Norwegian building practice and industry history and extend the museum’s research to include buildings from the recent past. Aluminum, steel, and glass were becoming more advanced and available in a wider variety of forms in the 70s and 80s. I wish to shed light on the lack of knowledge about preserving these materials and buildings. How does one preserve a building that does not age “gracefully”? And as a museum is almost the definition of permanence, how can one incorporate a building which is intended to be temporary and interchangeable into a museum collection without ruining its essence?

Mobile Heritage: Preserving Architecture on the Move is an architectural research project more than a conventional design diploma. It is also a preservation project centered on the quest of moving the office pavilion to a new destination, involving several design tasks and decisions. Essentially, the diploma is an argument for why a chosen building should be preserved combined with a strategy for doing it. This takes the form of a preservation plan.

Tora Lie Brunborg / +47 92322863 / tora.brunborg@gmail.com

Asker og Bærums Budstikke, 7. July 1990

Around midnight, a Tuesday in July 1990, a 107 square meter silver box of steel, aluminum, and glass, colloquially called the UFO, took off to a new destination, blocking the E18 Highway in the process. A service module was disconnected before the 10-ton building was lifted by a crane and onto a truck, and three hours later, 700 meters down the road, it landed on its new foundation. The spectacular event, which was extensively documented, with journalists referring to it as something out of a science fiction movie, is the starting point for my diploma project.

Because of the development of Lysakerlokket, a large-scale infrastructural project, Njål R. Eide’s eye-catching architectural office was forced to move elsewhere. Eide initiated the pavilion in 1978 as a prototype for large modular buildings for his two primary sectors of operation: cruise ships and oil platforms. An optimistic belief in a future where technology and mass fabrication played an important role was incorporated into the design. The office pavilion rested on four concrete pillars, 60 cm above ground, on leased land. It had a 25-square-meter service module connected to it, containing an entrance area, technical installations, and water. The office pavilion was built to move.

The unusual event on E18 more than 30 years ago is relevant for an architectural project today because the building in question is an unresolved issue – it currently lies vacant and derelict with no future plan. I will reveal through my diploma project that the building reflects a fascinating, multi-layered history. It is an heirloom from the recent past with a direct link to the oil industry and Norwegian cruise-ship design, two problematic fields which have shaped Norwegian society from the 1970s onwards. The pavilion’s history as a preservation object on the move also connects it to heritage management, a field in which preserving by moving has been a recurring method since the ambitious attempts to save national treasures such as stave churches and other vernacular buildings in the 19th century, leading to open-air museums, with Folkemuseet, located in Bygdøy, Oslo, as one internationally prominent example.

Eide’s portable office building is not a national icon but a style representative. If we are to nurture a holistic culture of reuse, more buildings from the recent past must be preserved and repurposed. This diploma asks how to restore, reuse, transform or dismantle this and similar structures. I propose to move the office pavilion once again to explore its potential for survival and repurposing. Reactivating a concept of mobility as a source of architectural design and a preservation strategy, the project links the office pavilion to past ideas that might be as valid today as ever.

From Arnstein Arnebergvei 31 to Folkemuseet

Today, the building appears as a futuristic ruin - dusty, dilapidated, with punctured windows and full of mold. Forty-four years have passed since its erection, thirty-two years since it was moved, and ten years since it was abandoned. Lysaker is yet again under development, and the building (together with Eide’s archive) and all its surroundings are planned for demolition to make room for new buildings. The easy thing would be to destroy it and forget about it. So why shouldn’t we?

My diploma project proposes moving the building to Folkemuseet as an ex-situ preservation tactic. This will emphasize its importance in Norwegian building practice and industry history and extend the museum’s research to include buildings from the recent past. Aluminum, steel, and glass were becoming more advanced and available in a wider variety of forms in the 70s and 80s. I wish to shed light on the lack of knowledge about preserving these materials and buildings. How does one preserve a building that does not age “gracefully”? And as a museum is almost the definition of permanence, how can one incorporate a building which is intended to be temporary and interchangeable into a museum collection without ruining its essence?

Mobile Heritage: Preserving Architecture on the Move is an architectural research project more than a conventional design diploma. It is also a preservation project centered on the quest of moving the office pavilion to a new destination, involving several design tasks and decisions. Essentially, the diploma is an argument for why a chosen building should be preserved combined with a strategy for doing it. This takes the form of a preservation plan.

Tora Lie Brunborg / +47 92322863 / tora.brunborg@gmail.com